- Photo Safaris

- Alaska Bears & Puffins World's best Alaskan Coastal Brown Bear photo experience. Small group size, idyllic location, deluxe lodging, and Puffins!

- Participant Guestbook & Testimonials Candid Feedback from our participants over the years from our photo safaris, tours and workshops. We don't think there is any better way to evaluate a possible trip or workshop than to find out what others thought.

- Custom Photo Tours, Safaris and Personal Instruction Over the years we've found that many of our clients & friends want to participate in one of our trips but the dates we've scheduled just don't work for them or they'd like a customized trip for their family or friends.

- Myanmar (Burma) Photo Tour Myanmar (Burma) Photo Tour December 2017 -- with Angkor Wat option

- Reviews Go hands-on

- Camera Reviews Hands-on with our favorite cameras

- Lens reviews Lenses tested

- Photo Accessories Reviews Reviews of useful Photo and Camera Accessories of interest to our readers

- Useful Tools & Gadgets Handy tools and gadgets we've found useful or essential in our work and want to share with you.

- What's In My Camera Bag The gear David Cardinal shoots with in the field and recommends, including bags and tools, and why

- Articles About photography

- Getting Started Some photography basics

- Travel photography lesson 1: Learning your camera Top skills you should learn before heading off on a trip

- Choosing a Colorspace Picking the right colorspace is essential for a proper workflow. We walk you through your options.

- Understanding Dynamic Range Understanding Dynamic Range

- Landscape Photography Tips from Yosemite Landscape Photography, It's All About Contrast

- Introduction to Shooting Raw Introduction to Raw Files and Raw Conversion by Dave Ryan

- Using Curves by Mike Russell Using Curves

- Copyright Registration Made Easy Copyright Registration Made Easy

- Guide to Image Resizing A Photographers' Guide to Image Resizing

- CCD Cleaning by Moose Peterson CCD Cleaning by Moose Peterson

- Profiling Your Printer Profiling Your Printer

- White Balance by Moose Peterson White Balance -- Are You RGB Savvy by Moose Peterson

- Photo Tips and Techniques Quick tips and pro tricks and techniques to rapidly improve your photography

- News Photo industry and related news and reviews from around the Internet, including from dpreview and CNET

- Getting Started Some photography basics

- Resources On the web

- My Camera Bag--What I Shoot With and Why The photo gear, travel equipment, clothing, bags and accessories that I shoot with and use and why.

- Datacolor Experts Blog Color gurus, including our own David Cardinal

- Amazon Affiliate Purchases made through this link help support our site and cost you absolutely nothing. Give it a try!

- Forums User to user

- Think Tank Photo Bags Intelligently designed photo bags that I love & rely on!

- Rent Lenses & Cameras Borrowlenses does a great job of providing timely services at a great price.

- Travel Insurance With the high cost of trips and possibility of medical issues abroad trip insurance is a must for peace of mind for overseas trips in particular.

- Moose Peterson's Site There isn't much that Moose doesn't know about nature and wildlife photography. You can't learn from anyone better.

- Journeys Unforgettable Africa Journeys Unforgettable -- Awesome African safari organizers. Let them know we sent you!

- Agoda International discounted hotel booking through Agoda

- Cardinal Photo Products on Zazzle A fun selection of great gift products made from a few of our favorite images.

- David Tobie's Gallery Innovative & creative art from the guy who knows more about color than nearly anyone else

- Galleries Our favorite images

Introducing Lytro: Will it make your camera a dinosaur?

Introducing Lytro: Will it make your camera a dinosaur?

Submitted by David Cardinal on Fri, 10/21/2011 - 15:12

Almost everyone agrees that the first consumer light field camera -- launched by start-up Lytro this week -- is as revolutionary as Foveon's launch of a true 3-color camera. If it lives up to the expectations of its founder and investors it is the future of cameras and will make the current models essentially obsolete. Light field technology is amazing, just like Foveon's, but it also has plenty of issues that remain to be ironed out. We'll give you the low-down on the technology, the new camera, and the issues…

Almost everyone agrees that the first consumer light field camera -- launched by start-up Lytro this week -- is as revolutionary as Foveon's launch of a true 3-color camera. If it lives up to the expectations of its founder and investors it is the future of cameras and will make the current models essentially obsolete. Light field technology is amazing, just like Foveon's, but it also has plenty of issues that remain to be ironed out. We'll give you the low-down on the technology, the new camera, and the issues…

First, what the heck is a light field? Simplistically, it is a means of recording the direction light is traveling when it reaches your sensor, in addition to its intensity. By knowing the design of the lens and the direction from which the light is hitting the sensor the camera can estimate the distance of the object which is reflecting the light. This gives a kind of "3-d" version of the scene.

“Living Picture” Sample –Click to Focus, Double-click to zoom

Photo by Eric Cheng / Lytro

Most importantly, capturing a light field allows the image to be focused and re-focused after the fact. Using some very fancy math it is possible to selectively focus on different areas of the scene, and de-focus other areas once you've captured a light field -- or simply to make it possible to shoot without worrying too much about focus.

Rather than trying to explain how cool this ability is, I'll encourage you to check it out online using some of Stanford's public light field images and online Flash-based viewer. You can focus in on any part of the chess board after the fact.

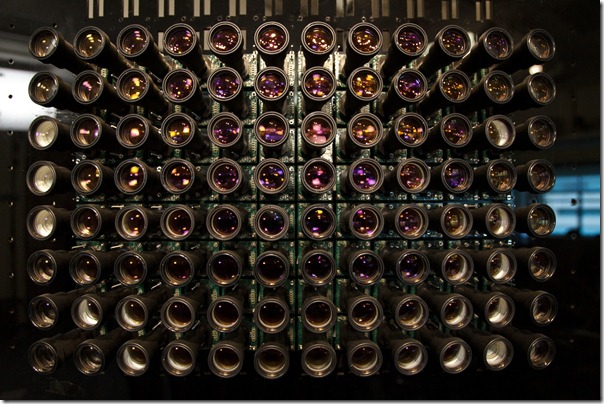

Stanford plenoptic camera array used to research light fields

Stanford plenoptic camera array used to research light fields

Until now light fields were confined to researchers with expensive, custom equipment, like the pictured Stanford camera array above. But startup Lytro, the brain-child of plenoptic camera prodigy Ren Ng, has introduced a $399 "point and shoot" which captures limited, but usable, light fields in a slick and small form factor.

Ren's version of the future has light field photography rendering traditional "2-d" image capture obsolete. Certainly in an absolute sense more information is better than less, so why not capture additional information, in a perfect world? The devil is in the details. Much like the Foveon 3-layer sensor was hyped to replace the more familiar single-layer Bayer array in use today, light field photography has some drawbacks.

First and most obvious is that the light field itself is a particularly inscrutable kind of raw file, and requires substantial processor power to turn into a shareable JPEG or TIFF. So, like the early Foveon cameras, the first generation of Lytro cameras don't capture JPEGs. They only create light field files which require their software to process on a computer. Their software will at first be Mac-only, but with a Windows port set to follow fairly quickly.

Because light fields are an active area of research, and Adobe has been involved in light field projects, I'd expect that over time the light field files will be directly usable in some version of Photoshop Extended, for those willing to shell out the dollars for Adobe's high end tools. Ideally it'd be available, at least as a plug-in, for Photoshop Standard and Photoshop Elements.

The blue and gray versions have 8GB of storage for $399,

The blue and gray versions have 8GB of storage for $399,

the Red model has 16GB for $499, pre-orders are being taken now.

The next drawback is resolution. To gather directional data at each location on the sensor a plenoptic camera uses a microlens array in front of the sensor to split the light arriving at the sensor by direction into individual pixels. This means that each effective pixel must cover several underlying pixels. That's a little hard to explain, but in short in simplest terms if you want to have control over 4 stops of DOF (from f/2 to f/8, for example) you might need as many as 16 pixels for each effective pixel -- reducing the resolution of a 16MP sensor to 1MP.

Lytro has spent years working on these issues so I'm sure they are doing better than the simple implementation we've described, but at the launch they were careful to describe the camera as 11 "Mega-rays" (which we can assume are the actual pixels on the sensor -- each recording a position and direction) with an effective resolution of at least 1080 pixels (not much more than 1MP, since the image produced by the camera is square).

Note that the additional depth needed for the micro-array makes it very unlikely that a light field capability can be retrofit into existing Nikon or Canon bodies or current form factor. This capability will need to really take the world by storm before it is likely that any of the really big companies decide to dedicate camera models to it -- the same issue faced by Foveon until their purchase by Sigma.

Using the camera

The camera has a unique form factor, holding its 8x zoom lens (approximately 35mm – 280mm equivalent) inside the elongated body, which is shaped for holding like a small spyglass or spotting scope. There are no external controls, with the controls embedded under the rubberized portion of the camera, consisting of an on/off switch, a zoom control, and a shutter. You can also zoom by pressing the small touch screen at the end of the camera. One handed shooting will be pretty simple as a result, but the form factor will probably cause consternation for many photographers used to holding their cameras firmly with both hands. A tripod attachment accessory is planned for the future.

Not needing to focus lets the Lytro not only start nearly instantly but capture images very quickly. Of course cameras like the Olympus E-P3 and even the iPhone 4S can do this also, making the Lytro's speed less unique then it would have been a year ago.

The Lytro doesn't have removable storage. So after you've shot about 350 images on the 8GB model, or 750 on the 16GB model, you need to connect it over USB to your computer (initially only Macs are supported, with Windows to follow) and upload the images before you can take more.

Should you buy one?

Lytro 3D Living Picture Demo Video

If you want to have another cool camera to play with, by all means. There is no question that the nearly zero shutter lag, space age design, and spell-binding ability to focus and re-focus your images after the fact will be compelling for many early adopters. However, having to process all your images on the computer, the limited resolution, and a complete lack of video capture will make the initial Lytro versions an unlikely choice for anyone only wanting to carry one point and shoot.

Are light fields the future?

This is a tough one. As a way to allow for selective focus after the fact, light fields are the best game in town. But for many users what they really want is the convenience of not having to worry about focus and have their entire image be sharp. It turns out there are simpler ways to address that issue. By having a specially designed "logarithmic" lens which varies its refractive index across its width, it is possible to build lenses with greatly increased depth of field. Robotics and cellphone camera companies have actively been pursuing this research and products using that technology.

- Log in to post comments