- Photo Safaris

- Alaska Bears & Puffins World's best Alaskan Coastal Brown Bear photo experience. Small group size, idyllic location, deluxe lodging, and Puffins!

- Participant Guestbook & Testimonials Candid Feedback from our participants over the years from our photo safaris, tours and workshops. We don't think there is any better way to evaluate a possible trip or workshop than to find out what others thought.

- Custom Photo Tours, Safaris and Personal Instruction Over the years we've found that many of our clients & friends want to participate in one of our trips but the dates we've scheduled just don't work for them or they'd like a customized trip for their family or friends.

- Myanmar (Burma) Photo Tour Myanmar (Burma) Photo Tour December 2017 -- with Angkor Wat option

- Reviews Go hands-on

- Camera Reviews Hands-on with our favorite cameras

- Lens reviews Lenses tested

- Photo Accessories Reviews Reviews of useful Photo and Camera Accessories of interest to our readers

- Useful Tools & Gadgets Handy tools and gadgets we've found useful or essential in our work and want to share with you.

- What's In My Camera Bag The gear David Cardinal shoots with in the field and recommends, including bags and tools, and why

- Articles About photography

- Getting Started Some photography basics

- Travel photography lesson 1: Learning your camera Top skills you should learn before heading off on a trip

- Choosing a Colorspace Picking the right colorspace is essential for a proper workflow. We walk you through your options.

- Understanding Dynamic Range Understanding Dynamic Range

- Landscape Photography Tips from Yosemite Landscape Photography, It's All About Contrast

- Introduction to Shooting Raw Introduction to Raw Files and Raw Conversion by Dave Ryan

- Using Curves by Mike Russell Using Curves

- Copyright Registration Made Easy Copyright Registration Made Easy

- Guide to Image Resizing A Photographers' Guide to Image Resizing

- CCD Cleaning by Moose Peterson CCD Cleaning by Moose Peterson

- Profiling Your Printer Profiling Your Printer

- White Balance by Moose Peterson White Balance -- Are You RGB Savvy by Moose Peterson

- Photo Tips and Techniques Quick tips and pro tricks and techniques to rapidly improve your photography

- News Photo industry and related news and reviews from around the Internet, including from dpreview and CNET

- Getting Started Some photography basics

- Resources On the web

- My Camera Bag--What I Shoot With and Why The photo gear, travel equipment, clothing, bags and accessories that I shoot with and use and why.

- Datacolor Experts Blog Color gurus, including our own David Cardinal

- Amazon Affiliate Purchases made through this link help support our site and cost you absolutely nothing. Give it a try!

- Forums User to user

- Think Tank Photo Bags Intelligently designed photo bags that I love & rely on!

- Rent Lenses & Cameras Borrowlenses does a great job of providing timely services at a great price.

- Travel Insurance With the high cost of trips and possibility of medical issues abroad trip insurance is a must for peace of mind for overseas trips in particular.

- Moose Peterson's Site There isn't much that Moose doesn't know about nature and wildlife photography. You can't learn from anyone better.

- Journeys Unforgettable Africa Journeys Unforgettable -- Awesome African safari organizers. Let them know we sent you!

- Agoda International discounted hotel booking through Agoda

- Cardinal Photo Products on Zazzle A fun selection of great gift products made from a few of our favorite images.

- David Tobie's Gallery Innovative & creative art from the guy who knows more about color than nearly anyone else

- Galleries Our favorite images

360-degree photos, Virtual Reality, and what they mean for photographers: Some thoughts

360-degree photos, Virtual Reality, and what they mean for photographers: Some thoughts

Submitted by David Cardinal on Mon, 03/28/2016 - 13:23

With the sudden interest in 360-degree photos and videos – along with a variety of new products for capturing them – it is natural to ask how they will be viewed, and what they might mean for photographers. This is a rapidly-changing area, but with today’s official launch of the Oculus Rift VR headset, it’s a good time to take stock of where we are so far – both in image capture and viewing.

With the sudden interest in 360-degree photos and videos – along with a variety of new products for capturing them – it is natural to ask how they will be viewed, and what they might mean for photographers. This is a rapidly-changing area, but with today’s official launch of the Oculus Rift VR headset, it’s a good time to take stock of where we are so far – both in image capture and viewing.

Capturing 360-degree photos and videos

The simplest way to capture a 360-degree photo is to use an app on your smartphone. Most smartphones now ship with the ability to capture “photospheres” built-in, or you can download a camera app to do so. You simply move your phone around as instructed by the device, and it fills in a full spherical image of everything around you. As you might expect from such a simple approach, there are lots of imaging artifacts, especially if lighting is uneven. Stitches between the individual images are also pretty obvious.

Specialized 360-degree cameras are designed both to improve the output, and to allow realtime capture – thus enabling 360-degree video. Until recently these were mostly aimed at high-end commercial operations, and included the Samsung Beyond and the Google Project Jump models – both priced in the many thousands of dollars. The Ricoh Theta, available for under $350, was one of the few models aimed at consumers.

Specialized 360-degree cameras are designed both to improve the output, and to allow realtime capture – thus enabling 360-degree video. Until recently these were mostly aimed at high-end commercial operations, and included the Samsung Beyond and the Google Project Jump models – both priced in the many thousands of dollars. The Ricoh Theta, available for under $350, was one of the few models aimed at consumers.

Unfortunately, using a single camera to capture a full spherical image at once means a loss of apparent resolution, especially away from where the lenses are pointed. So for serious content creators, multiple camera rigs are here to stay. In the meantime, though, Nikon and others have announced products aiming at the action camera market that will record a 360-degree perspective around whatever adventure you’re undertaking. The Nikon KeyMission 360 4K action camera announcement generated quite a lot of buzz at CES, but pricing and availability haven’t been announced. So far all of GoPro’s 360 capture solutions involve combining multiple individual cameras, but I’m sure that will also change.

Viewing 360-degree content

While most 360-degree content is currently viewed on regular computer or mobile device screens, either using a mouse to move around, or the device’s gyroscope to let the viewer move around more naturally. But in both cases, the viewer is only seeing a small portion of the image and not in a particularly “life like” way. That’s where VR viewing devices come in. Once seen through a VR device, the scene in front of the viewer takes on the same field of view as if you were in the middle of it. Looking around becomes a simple matter of moving your head. With higher-end devices that also offer head tracking, you can move closer to one part of the image as well. Unfortunately, while all that sounds great on paper, each of the three major ways of viewing 360 content in VR has some practical issues:

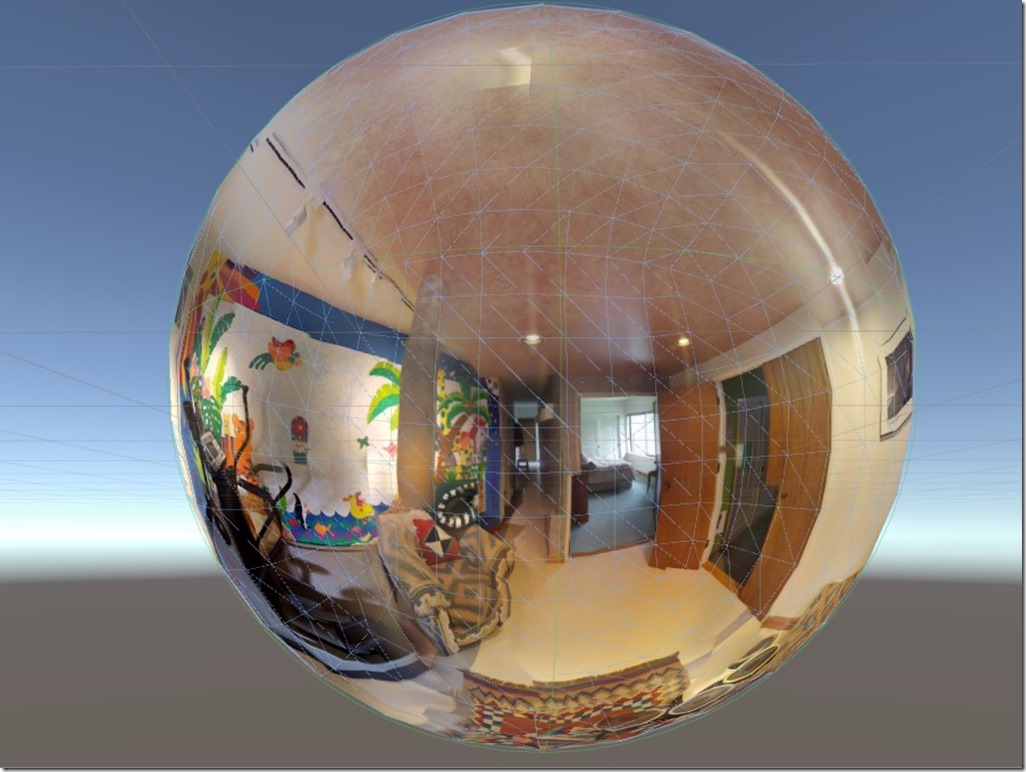

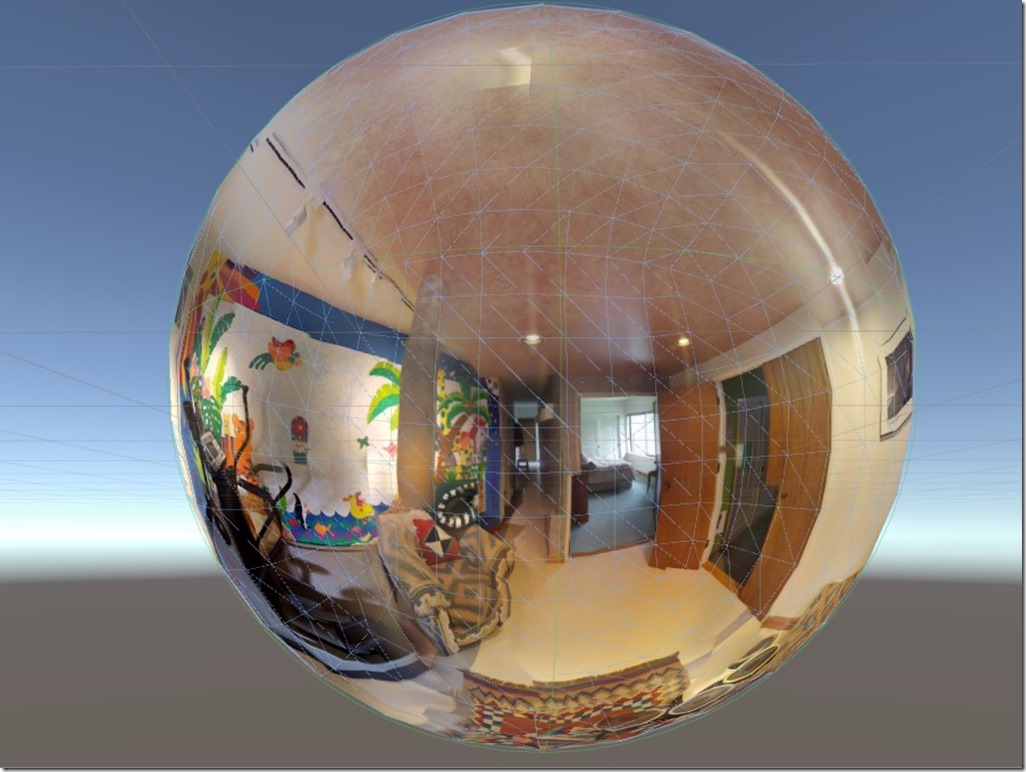

Here is what a 360-degree photosphere looks like from the outside

Looking at 360-degree content through Google Cardboard

Cardboard (and VR) made a big splash when the New York Times included one with all million copies of its newspaper, along with some custom 360-degree content that you could download. Around the same time Sundance Film Festival made its 360-degree and other VR content temporarily free. The result has been millions of hours of VR viewing online through what is definitely the cheapest possible solution (you can get a Cardboard for about $20 – it then uses your smartphone to do all the work). The great thing is that it has gotten a lot of people exposed to VR that otherwise would not have been. The downside is that most phones aren’t powerful enough, or have high-enough resolution displays, to really do the format justice, or make the images look as impressive as they would if you were staring at them on a traditional monitor.

Cardboard (and VR) made a big splash when the New York Times included one with all million copies of its newspaper, along with some custom 360-degree content that you could download. Around the same time Sundance Film Festival made its 360-degree and other VR content temporarily free. The result has been millions of hours of VR viewing online through what is definitely the cheapest possible solution (you can get a Cardboard for about $20 – it then uses your smartphone to do all the work). The great thing is that it has gotten a lot of people exposed to VR that otherwise would not have been. The downside is that most phones aren’t powerful enough, or have high-enough resolution displays, to really do the format justice, or make the images look as impressive as they would if you were staring at them on a traditional monitor.

Look for Google to push the envelope here with a successor to Cardboard at its IO Conference in mid-May. It’ll be interesting to see how far they can move the low-end of the market forward.

Gear VR: Awesome VR starter kit if you have the right smartphone

If you have one of the few high-end Samsung Galaxy smartphones that work with Gear VR, it is a great way to get started. At $100 (or free if you buy a new Galaxy S7 with it bundled), it offers a viewing experience not all that much worse than the much more expensive VR headsets (however, it doesn’t have its own Audio, or support head movement tracking, or many of the other features you get with an Oculus or HTC device). One big advantage of Gear VR over Cardboard is that it has an integrated touchpad and volume control, so you can interact more easily with content and menus on the device.

Oculus Rift, HTC Vive, or PlayStation VR

There are at least three major “high-end” VR headsets scheduled to ship this year. The first out is the long-awaited Oculus Rift, a $599 package of headset, remote, gamepad, and integrated 3D audio headphones. It also has an exterior sensor to allow head position tracking. Aside from the price (and need for lots of cabling), the biggest downside is that it only works on seriously-beefy Windows PCs. So for now, unless you’re a hardcore gamer and want to immerse yourself in VR games, you’re better off finding someplace where you can demo one. The HTC Vive is even more expensive, at $800, but will include two whizzy Touch controllers (Oculus will be pricing those separately when they are available). The Oculus is back-ordered until July and the Vive is supposed to start shipping in May. Sony’s PlayStation VR is the newest entry on the list, and the least expensive – at $399 or $499 as part of a bundle with wireless controllers. Of course, you’ll need to supply your own PlayStation, at least until Sony adds support for PCs.

There are at least three major “high-end” VR headsets scheduled to ship this year. The first out is the long-awaited Oculus Rift, a $599 package of headset, remote, gamepad, and integrated 3D audio headphones. It also has an exterior sensor to allow head position tracking. Aside from the price (and need for lots of cabling), the biggest downside is that it only works on seriously-beefy Windows PCs. So for now, unless you’re a hardcore gamer and want to immerse yourself in VR games, you’re better off finding someplace where you can demo one. The HTC Vive is even more expensive, at $800, but will include two whizzy Touch controllers (Oculus will be pricing those separately when they are available). The Oculus is back-ordered until July and the Vive is supposed to start shipping in May. Sony’s PlayStation VR is the newest entry on the list, and the least expensive – at $399 or $499 as part of a bundle with wireless controllers. Of course, you’ll need to supply your own PlayStation, at least until Sony adds support for PCs.

For 360-degree content, a dedicated VR headset might be overkill, but the greater horsepower of being tethered to a PC allows for on-demand rendering, and therefore more complex types of immersive content – where you can wander around a scene or interact with characters and objects.

What about 3D?

While the experience of looking at a 360-degree video through a VR headset can feel like 3D, it often isn’t. To provide actual 3D, the capture device needs to either directly support stereo recording (typically with two cameras facing each direction), or use some type of image processing magic (like OmniStereo) that still requires either multiple cameras or multiple frames. Currently there aren’t any affordable devices that offer stereo 3D image capture in real time, so the best most photographers will be able to do is single image 360-degree photos and videos.

What’s “immersive” content, and how is that different?

So far, everything we’ve talked about is a passive experience, fairly similar to viewing a photo or video. But VR allows for much more than that, potentially including allowing the viewer to move through a scene, and interact with other people or objects. That requires even more specialized equipment and post-production (not to mention even more viewing horsepower), but promises that we will eventually have truly immersive experiences (remember the Star Trek Holodeck?)

Okay, so how do you use this stuff?

Getting the gear is only the beginning of the challenges with 360-degree story telling. First, there is nowhere to “hide” as the viewer can look everywhere, and see everything. Then there’s sound. It should really sound like it is directional, and depends on the viewer’s orientation. Composition also needs to be re-imagined, as the creator needs to find ways to direct the viewers’ attention within the scene. Making a plan for how an eye will move through a static 2D image is one thing, but doing it for an entire worldview is another. Stay-tuned for more articles on this topic over the coming months.

- Log in to post comments